Abstract

Recent research has suggested that betrayal trauma, where a child is an object of others’ violence, can lead to him or her becoming an aggressor later in life. Trauma and violence have been shown to be integrally linked. A shattered self leads to a shattered world through elements such as internalization, splitting, and identification.

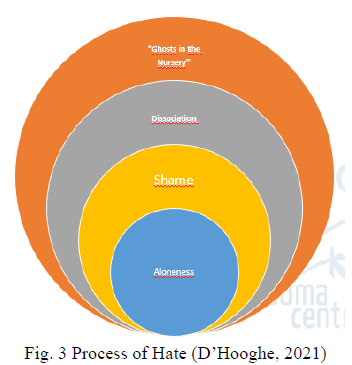

The process of hate begins with the splitting of the “good” from the “bad,” whereby the “bad” self is dissociated and projected onto the other. The other — the enemy — holds the qualities of the “bad” self and is demonized.

When we consider dissociated shame caused by trauma, then the shame-rage cycle can evoke the development of both intra- and interpersonal violence. The loneliness and separateness inherent in trauma are projected into the outer world and there simplify the polarization process of “I versus them.”

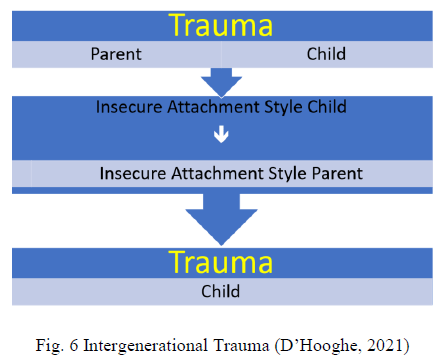

If the trauma experiences of members of a society are neither recognized nor healed, the effects of those experiences are passed on to the next generation and thus create intergenerational trauma. On an individual level, the unresolved past of the parents, set stage for intergenerational repetition of the traumatic experiences.

Trauma in society is re-enacted in the form of, for example, abuse, rape, and criminality. Therefore, the focus of trauma and peacebuilding must be directed toward an intra- and interpersonal transformation, and the domains of psychology and society. If we develop a relationship with our inner suffering, we can recognize our shared humanity which means the suffering of all human beings.

Bio-psycho-social-spiritual work is at the core of healing intergenerational trauma. On a societal level, the recognition of trauma, grief work, development of life skills, improvement of security, and belonging is crucial. On an intra-personal level, the critical elements are regaining safety, dignity, spirituality, building resilience, restoring body/brain functioning, and installing reconciliation. When healed, trauma survivors play a key role in peacebuilding.

What is trauma?

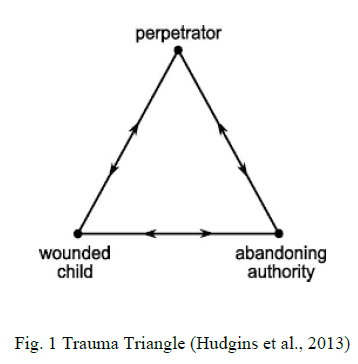

Trauma has been considered from three points of view: events, experience, and effects (SAMHSA, 2014). Events can be caused by impersonal (natural) or man-made stressors. Concerning man-made stressors, it has been proven important to make a distinction between trauma caused by an unknown person or by a known person. When man-made trauma refers to trauma caused by someone familiar, it has been shown to be more distressing and result in more psychopathology than natural disasters (Breslau et al., 1991). For example, when a child has been threatened, rejected, or not understood by a parent, the situation feels like betrayal. Given that the young child’s survival and emotional development is completely dependent on his or her parent’s behavior and way of relating to the child, the child becomes blind to the betrayal to preserve the attachment relationship (J.J. Freyd, 1995). As a consequence, the child becomes stuck in the drama triangle (fig.1) with an inability to escape since the child is unable to recognize danger or the perpetrator, or remember what happened.

Empty Toolbox

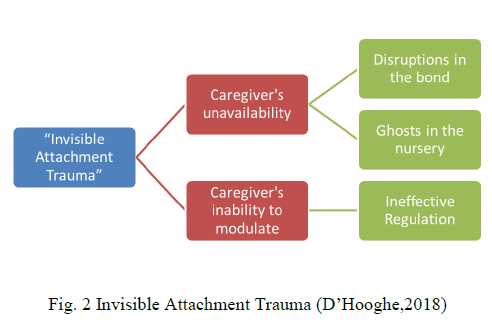

In the presence of attachment trauma and especially invisible attachment trauma (fig. 2), where the parent lacks the necessary skills to build a safe attachment relationship with the child, there is no development of affect-stress regulation capabilities, no sense of self, and dissociation, among others, therefore, the child is left with limited coping skills — “an empty toolbox” — to address subsequent traumatic experiences and is thereby prone to revictimization.

Pathways Towards Fragmentation

Aloneness

A sense of belonging has been shown to be an important human need. Innately, we are prepared to form and maintain relationships (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), and are hardwired to connect (Siegel, 2010). An insecure attachment relationship means the need to belong has not been met and the search for belonging is therefore ongoing. As a result, a tendency to create an enemy has been found, with the goal to belong, as focusing anger on the perceived enemy connects and brings a group together. This stage is the beginning of a polarization process resulting in an “us and them” mentality (Keen, 1991). Examining the topic from a relational neurobiological point of view, the child’s brain is creating a catalogue of “safe and familiar” attributes of his or her clan (Perry, 2009, p. 247). In interactions with strangers, the stress response is activated. When the child is raised with ethnic or religious beliefs that dehumanize others, the stress reaction can be severe (Perry, 2009). One common stress reaction derived from the autonomic nervous system is the “fight” (Porges, 2011), which activates the person to conflict and even war.

Shame

In an insecure attachment relationship, it has been found that if the child is embarrassed, ridiculed, or humiliated, his or her self-esteem will be low. When the attack is experienced as an injury to the self, a significant amount of shame is generated in the child. The child then replaces the internalized self-blame with blaming others — “what a horrible person you are doing that to me” — setting the stage for other-directed hostility, rage, and violence. Rage conceals shame by turning a passive shame state into an active, energy-loaden rage state. As a result, the child becomes trapped in the “shame-rage cycle” (Kohut, 1971/1976). A significant portion of the experienced shame is unaware, “unacknowledged shame” (Lewis, 1971), which disrupts the ability to feel shame or think clearly, and results in inappropriate responses. In these cases, the experienced pain has never been acknowledged and these children move into hate (Sunderland &Hancock, 2003).

Hate can be considered as low-level diminished rage, and when a child is locked in hate, he or she may become obsessed with revenge (Sunderland &Hancock, 2003). This hidden shame and these systems of threat can precede conflict between nations whereby both sides of the conflict feel threatened and shamed by the other and each escalates into a collective shame-rage cycle — a “war fever” (Scheff, 1987).

Dissociation

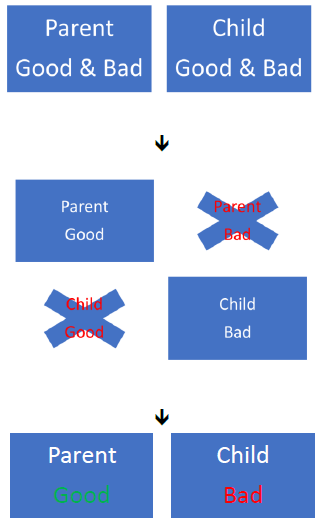

“The essential manifestation of pathological dissociation is a partial or complete disruption of the normal integration of a person’s psychological functioning” (Dell & O’Neil, 2009, p. xxi). Abandonment by parents, whether physical, psychological, or emotional, is one of the most feared situations for children. Totally dependent on their caregivers, children install mechanisms to stay close with their parents even when the attachment relationship is not safe. One of these mechanisms is the good-bad splitting. The child cannot live with the awareness that the parent’s behavior is damaging and causes anxiety, therefore, in his or her awareness, the child splits off the “bad” part in the parent and the “good” part in the self.

Fig. 4 Good-Bad Dichotomy (D’Hooghe, 2021)

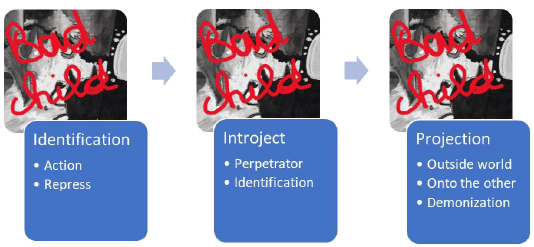

This splitting could potentially lead to three different manifestations of the dissociated “bad” part.

Fig. 5 Manifestations of Dissociated “Bad” Part (D’Hooghe, 2021)

Manifestations of Dissociated “Bad” Part (D’Hooghe, 2021)

1. Identification

The child identifies with the bad part in either an active way, which means acting out with negative behavior, or represses the bad part with which he or she is identified, resulting in suppressed anger.

2. Introjection

The child identified with the perpetrator introjects with the aim of holding the trauma out of consciousness and preserving the attachment relationship. The self of the child organizes around a sense of power, repeating the patterns of violence, blame, etc. It can be postulated that this concept can extend beyond the individual, whereby even a society that has experienced unresolved trauma can live a state of perpetration.

3. Projection

When children split from their bad part and project it onto the other, the other person becomes the enemy who holds all the bad aspects. This demonization process is the basis for further conflict and bloodshed (Ayalon, 2006).

“Ghosts in the Nursery” (Fraiberg et al.,1975)

Parent’s unresolved (attachment) trauma has been shown to interfere with the ability to build a secure attachment relationship with their child. The neurobiological impact of the parent’s unresolved trauma remains, causing high levels of stress, and these parents lack an emotion/stress regulation capability; further, the unresolved trauma causes specific interrelational patterns that are transmitted on a non-verbal level. Additionally, the “ghosts in the nursery” phenomenon prevents the development of the reflective functioning and mentalizing ability. Trauma between the caregiver and the child results in an insecure attachment style, which is carried into adulthood and parenthood.

Deriving from their own insecure attachment style, the parent is traumatizing the child (Fig. 6). It is likely that trauma is passed from one generation to the next in this manner, therefore, unresolved traumatic experiences are the basis of intergenerational trauma. We can state that unresolved individual trauma effects the community and, as such, societies can be transformed and create patterns of aggression, rape, and criminality. Furthermore, a society as a whole can be affected by trauma and react collectively. This reaction can be compared with an individual trauma response such as hyperarousal, anxiety, or violence (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, 2014)

Healing

Prevention as a Key Intervention (Isobel et al., 2018)

Consider that the unresolved traumatic history of parents leads to intergenerational trauma, it is evident that one key intervention would be healing parents’ unresolved trauma. A second important intervention would be assisting parents in building secure attachment relationships with their children.

Beginning in pregnancy and throughout the peri-natal period, screening for parental attachment skills would be a powerful preventive action. This could include screening for the parents’ “internal working model” (Bowlby, 1997), their ability to mentalize, the quality of the relationship between parents etc., because these capabilities underlie the development of a secure attachment relationship.

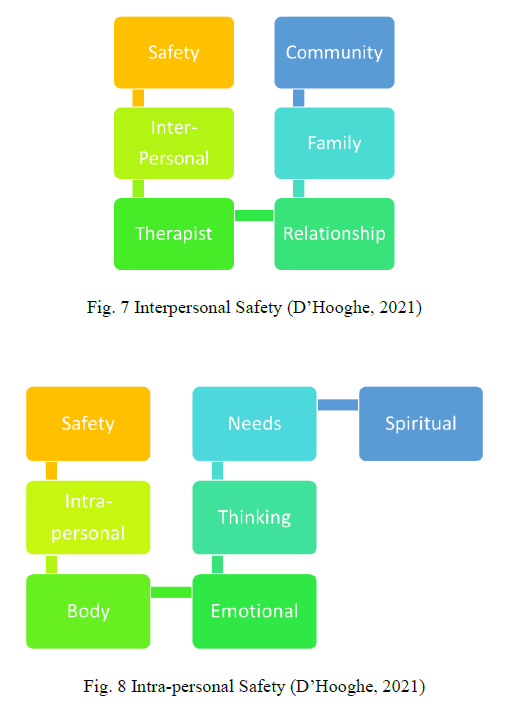

Creating safety

First, I wish to emphasize the necessity for considering safety as bi-directional, namely interpersonal safety (Fig. 7) and intra-personal safety (Fig. 8)

This installing of safety in both directions is a guiding theme throughout the peace model (D’Hooghe, 2021)

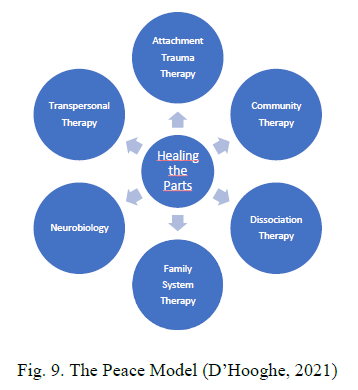

The Peace Model (Fig. 9)

The peace model is focused on breaking the circle of intergenerational trauma by healing the varied parts of the composition.

Attachment and Trauma Therapy

Healing Relationship

The majority of traumatic events have been found to occur between (familiar) people (man-made trauma), which appears to be more traumatizing than trauma caused by nonhuman elements. From an attachment and trauma-based approach, the first and most important element on the road to peace is the installation of a healing relationship, be it with a therapist or between parent and child, partners, family, or community. Further, reaching for healing relationships is an important goal to strive for between the inner parts of the self. The core elements in developing a healing relationship are the development of affect regulation, sensitive responsiveness, containment, mentalization, shared pleasure, and playfulness.

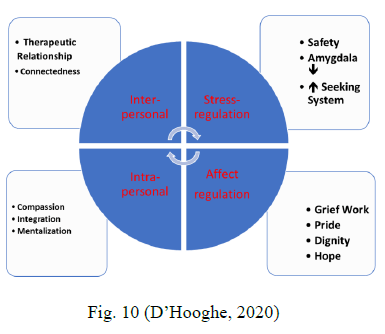

Shame

Shame has been shown to be an inherent consequence of attachment trauma, therefore, working with shame is a necessity for a person to come to peace. Mostly, shame under the surface can play a destructive game, because it is overlooked, unacknowledged, hidden, or acted out in an aggressive manner. The shame intervention model (D’Hooghe, 2020) is composed of four compartments, where one compartment focuses on calming the over-activated stress mechanism and enhancing the seeking system (Panksepp, 1998). One cannot work towards relationship building if the brain is still sending warning signals that the world and others are not safe. The affect regulation capability, learned in a safe attachment relationship, has been found to always be deficit in attachment trauma. Therefore, learning affect regulation strategies is an inevitable part of shame therapy.

On an interpersonal level, enhancing experiences of safety, attunement, and being understood, among others, has been demonstrated as the key to self-development and self-love. Such enhancement has been shown to create and fulfil the need to belong, while in opposite, the unmet need for security sets the stage for aloneness. Aloneness has been found as a likely cause leading to the polarization process of us and them. On an intra-personal level, dealing with criticism and self-blame helps integrate the necessary good parts on the way to peace. Part of the intra-personal work is enhancing the mentalizing capability so the person can truly see the other. Finally, if a person is enabled to contact his or her own suffering and recover from it, then he or she will be able to be sensitive to the suffering of others. Compassion is installed when a person, by going through his or her own healing process, can feel the deep commitment to try to relieve the pain of the other.

Shame Intervention Model (Fig. 10)

Grief

Unfinished grief has been shown to lead to the blocking of emotions, which renders empathy or intimacy impossible. Such a situation brings a person to a chronic hypo-aroused state with a significant amount of indifference and apathy towards the self and the other. Considering this state as a kind of detachment, no processing of the experienced trauma can take place. Acknowledging the pain and the loss experiences, and helping the person going through the mourning stages set the stage for recovery and peace.

Community Therapy

Trauma education for helpers such as psychologists and social workers has been considered a necessary part of the healing process, to ensure that traumatized people are not re-traumatized by the help they receive (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, 2014). Trauma-informed education includes realization of the impact of trauma and possible methods for healing, the recognition of trauma signs and symptoms, responding via establishing strategies and treatment pathways, and resistance of re-traumatization (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, July 2014). The six basic principles for a trauma-informed approach have been defined as safety; reliability, and transparency; peer support; collaboration and reciprocity; empowerment, Voice and Choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues (SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, July 2014).

Dissociation Therapy

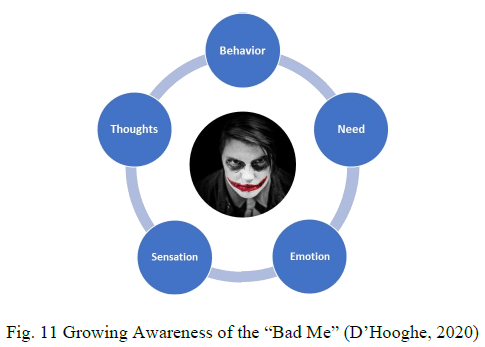

Good-bad Splitting

Arriving at peace in the inner self and in the world has been shown to be accomplished by working towards integration and wholeness. Modulating intense emotions occurring within the inner parts can be achieved by creating and contacting more compassionate and inner child areas holding safe and lovable experiences. In addition, enhancement of awareness and exploring the “bad me” are useful tools (fig. 11).

Helpers can guide the client in regulating emotions, restructuring thoughts, calming the stress mechanism, and satisfying needs. Further effective tools include building bridges in the internal world between the bad me and, for example, the inner advisor, the spiritual elements, the protector, and the nurturing part. The integration of both the dissociated good and bad part can connect a person with the most important ingredients for peace, which are love, mastery, self-determination, self-actualization, and belonging.

Integrate Human Needs.

In traumatized individuals, many of the human needs have been compromised. For example, the human need for security has been violated by the experienced danger inherent to trauma. Enhancing the sense of safety on an intra- and interpersonal level has been shown to be the basis for recovery. The unmet need for identity is often the initiator of conflict and even war. We need to distinguish oneself from another, acknowledging that each person possesses a unique identity that is not shared with others (Blumberg & Hare, 2006). By re-establishing the exclusive parts of the self, which can be assumed to be the core of a human being, people can connect through the experience of common humanity. The need for self-determination can be fulfilled by providing equal opportunities to all human beings (Blumberg & Hare, 2006).

When this need has been violated, conflict can occur in individuals and groups. To live a happy and healthy life, the need for well-being must be met, otherwise conflict can result (Blumberg & Hare, 2006).

Free the Dissociated Anger

It has been found that different parts of a person can hold varied emotions as accompaniments to the traumatic experiences. Anger is often suppressed and dissociated, living under the surface, resulting in passivity and shut down. Safely freeing the anger liberates the necessary energy to thrive and move on. Freeing the individual from the identification with the perpetrator within helps to distinguish the self from the anger. A useful strategy is to identify the dissociated anger, build contact with it and negotiate so this part is enabled to collaborate with other parts and becomes a resource instead of a danger.

System/Family Therapy

In a trauma-informed family treatment, the sense of safety for all family members has been demonstrated as primary. Therapy with the parents involves repairing the child-parent attachment bond, increasing the parent’s quality of parenting, healing the parent’s trauma and attachment history, and including parents in the healing process of their child. Aims of family therapy include, for example, building on family strengths, increasing mutual understanding, integrating needs, and enabling exploration and expression of their inner world by family members.

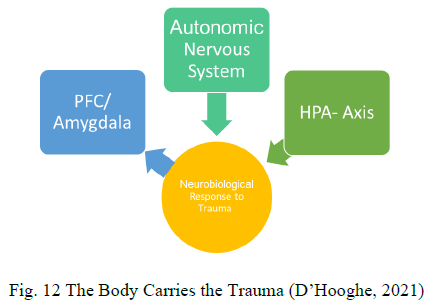

Neurobiology

A core component of trauma is anxiety. When trauma experiences are chronic, repeated, inescapable, and occur at a young age, the brain has been shown to be affected (fig. 12).

These long-lasting effects impact the development and functioning of the amygdala, which sends rapid signals to the body resulting in the fight/flight/shut down survival strategies of the autonomic nervous system. In this case, the limbic system (feelings) is cut off from the pre-frontal cortex (thinking). A significant number of traumatic experiences are stored in the limbic part of the brain, which means they are implicit and unable to be verbalized. The Broca’s area, responsible for the articulation of personal experience, deactivates during the traumatic event (Theberge, 2005). In this way, the inability to verbalize the traumatic experience leads towards somatization, wherein the sensory component of the trauma is recalled (van der Kolk et al., 1996). Due to such prolonged exposure to stress, the HPA-axis becomes used to the stress and maintains this activation with a continuous release of cortisol, therefore, this treatment part of the peace model is crucial. When traumatic experiences are repetitive, occurring over a long period, sequential, etc., the brain is shaped accordingly. The implementation of top down and bottom-up exercises are an inevitable part of the therapy in these situations. A range of somatoform-oriented therapies are included, together with meditation, visualization, and exercising, to unlock and integrate spirituality e.g., gratitude and love exercises.

Transpersonal Therapy

This holistic approach, with a great emphasis on spirituality, is a core element of the peace model. First, the integration of some parts of the self, e.g., love, dignity, forgiveness, and hope, which were hidden for survival purpose, is crucial to achieve wholeness and connectedness both with the self and the other. The experienced shared humanity by recognizing, expressing, and healing the pain of one and the other can shape peace globally. The forgiveness cycle (Tutu & Tutu, 2014) highlighted the importance of telling individuals’ stories and becoming seen in the pain as foundation for the enabling of granting forgiveness and relating again. Inspired by the dignity model (Hicks, 2011), the different aspects of dignity, such as acceptance of identity, understanding, and fairness, must be learned, implemented, and felt to finally results in peaceful connections.

My wish for the future.

May we never fail to strive for internal peace and world peace.

May we find hope and strength to never give up and to stand for all humans.

May we stay inspired from the heart to act with dignity and love.

May we, in the end, be peaceful with one another.

References

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Blumberg, H. H., & Hare, P. A. (2006). Peace Psychology (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bowlby, J. (1977). The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds. British Journal of Psychiatry, 130(5), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.130.5.421

Breslau, N., & et al. (1991). Traumatic Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in an Urban Population of Young Adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48(3), 216. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003

Dell, P. F., & O’Neil, J. A. (2009). Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders. DSM-V and beyond. Taylor & Francis.

D’ Hooghe, D. (2017). Seeing the Unseen- Early Attachment Trauma and The Impact on Child’ s Development. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behaviour, 5(1), 4-7. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000326

D’Hooghe, D. (2018, April 24). I Love You, My Killer: “Invisible” Attachment Trauma Resulting in Adult Traumatic Bonding and Healing Strategies- ISSTD 35th Conference- Bridges to the future – USA- Chicago.

D’Hooghe, D. (2020, May). “Despicable me”: Dissociative Shame in Children Resulting from Attachment Trauma. A journey towards Wholeness. Download Despicable Me -ISSTD 2020.pdf

D’Hooghe, D. (2021, April). “How Peace Can be Shaped by Healing the Fragmented Self” ( [Workshop]. ISSTD 38th Annual International Conference, Virtual, USA.

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the Nursery. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421. Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hicks, D. (2011). Dignity (1st ed.). Yale University Press.

Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., Furness, T., & Foster, K. (2018). Preventing intergenerational trauma transmission: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14735

Keen, S. (1991). Faces of the Enemy: reflections of the hostile imagination. Harper

Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorder. International Universities Press. Kohut, H. (1977). The Restoration of the Self. New York: International Universities Press. Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and Guilt in Neurosis. New York: International Universities Press.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press.

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining Child Maltreatment Through a Neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical Applications of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(4), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903004350

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and elf-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton.

SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. (2014, July). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. SAMHSA. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content

Scheff, T. J. (1987). The shame-rage spiral: A case study of an interminable quarrel. In H. B. Lewis (Ed.), The Role of Shame in Symptom Formation (pp. 109–149). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). Mindsight. Penguin Random House.

Sunderland, M., & Hancock, N. (2003). Helping Children Locked in Rage or Hate (New ed). Taylor & Francis.

Theberge, A. (2005). The Neurobiological and Neuroendocrine Underpinnings of Complex Trauma and Complex PTSD. https://www.academia.edu/35111057/The_Neurobiological_Underpinnings_of_Complex_PTSD

Tutu, M., & Tutu, M. (2014). The Book of Forgiving. HarperOne.

van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C., & Weisaeth, L. (Eds.). (1996). Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body, and society. The Guilford Press.