Written by Layla Brack.

Working in the same practice as Doris D’Hooghe, she inspires me daily, as she has come up with integrations of different theories and new perspectives on existing literature. She also introduced ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’ in some of her workshops, which is a term that has not been used before in our field and which is the topic of this review.

The definition of ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’ begins in the understanding of the parent-child relationship. In 1951, John Bowlby introduced the attachment theory, where both he and Mary Ainsworth emphasized the importance of a parent being sensitive and responsive towards a child. This attunement allows a secure attachment to be formed between the parent and child. Sensitivity mostly refers to

the correct response, being attuned to the specific needs of the child, whereas responsivity refers to the speed used at which a parent responds to his or her child (Bowlby, 1951; Ainsworth, 1978).

Many researchers followed Ainsworth and Bowlby their path by investigating the role of parental skills. In her workshops, D’Hooghe (2020) selected a set of necessary parental skills in order to gain the ability to be sensitive and responsive to a child’s needs. She not only singled these skills out, but also put them in a specific order that would help someone master this skill set. Firstly, it is important for a parent to be able to understand the mental experiences of his child, rather than to focus on the child’s behavior only. This is called ‘mentalization’ (Fonagy etal., 2002). The next step is ‘reflective functioning’. D’Hooghe refers to this skill as the ability to understand the child’s mental experience (mentalization) and, at the same time, observe one’s own internal experiences. This allows one to acknowledge, as Selma Fraiberg and colleagues (1997) described it, ‘ghosts in the nursery’ on the one hand and mirror the child’s feelings in a congruent manner on the other hand. Next, D’Hooghe tackles ‘containment’, the ability to cope with both your own, as well as the child’s emotions (Bion, 1962). A contained response means that a parent can reflect upon and regulate his own internal reaction in response to the child’s attachment behaviors, leading to the regulation of the child’s experiences. Lastly, there is the importance of ‘play’. Play creates an environment where positive interactions take place in which the parent can apply these skills and serve as an external regulator for the child (Schore & Schore, 2007). The child is learning regulation through his parent’s reaction. These parental skills are part of the development of a sensitive and responsive reaction and thus, help contribute to a safe attachment of the child to its parents.

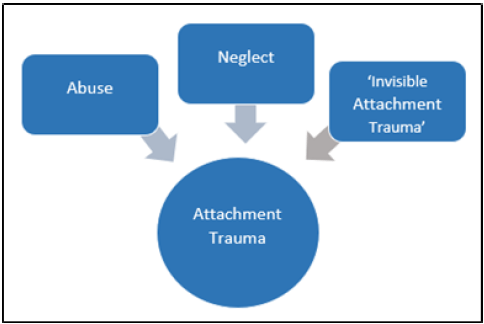

If a parent is not able to respond adequately to the child’s attachment behavior, the parent is emotionally unavailable which is equal to the absence of a parent (Beverly, 1994). Much research describes this kind of trauma as attachment trauma, which is an overarching term that refers to all traumatic experiences between a parent and its child (Allen, 2018). In most of said research, abuse or neglect are mentioned, however, there is rarely a reference to the lack of sensitivity and responsiveness in the parent-child interaction. D’Hooghe (2018) emphasizes the importance of it and refers to ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’, shown in picture one. Besides abuse and neglect of a child, the inaccessibility of a parent can have the same impact as the actual loss of a parent (Beverly, 1994). It is safe to say that this inaccessibility can also be described as a traumatic experience, yet in a very covered manner because the signs are not as visible as compared to those of abuse or neglect. That is why Doris calls it ‘Invisible

Attachment Trauma’.

Figure one. Attachment trauma as an effect of abuse, neglect and‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’.

In our practice at Traumacenter Belgium, Doris and I encounter lots of patients who are victims of this ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’. They often believe that their experience is not worth being referred to as ‘traumatic’. They often do not have the narrative or memory to explain how traumatizing their experience is, because trauma is not always one big event that everybody understands the same and

agrees to call traumatic. Any series of experiences where the child’s needs are not met and where a child does not feel safe in the parent-child relationship causes a covert trauma. The lack of parental attunement is possibly an experience every person has at least once in their life. However, it is not a one-time event but the repetition of the unsafe feeling which causes an insecure attachment and likely posttraumatic symptoms, as seen in our clinical practice.

This dissertation argues that ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’ should be understood and recognized not only in accordance with abuse and neglect but also in accordance with parents lacking the necessary parenting skills to build a secure attachment relationship with their child. All these issues can lead to posttraumatic stress and must be taken into consideration. Both psycho- and neuroeducation are an important part of therapy and healing. Therefore, it is important that our clients are taught about the existence and the severity of ‘Invisible Attachment Trauma’.

Biography

- Ainsworth, M. (1978). Infant-Mother Attachment. American Psychologist, 34 (10), 932-937.

- Allen, J. (2018). Mentalizing in the Development and Treatment of Attachment Trauma. Routledge, New York, NY. ISBN: 879-1-78049-091-5.

- Beverly, J., (1994) Handbook for Treatment of Attachment-trauma Problems in Children. The free press, New York. Isbn: 0029160057

- Bion, (1962). The psychoanalytical study of thinking. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 43, 306-10.

- Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization Monografh, 2, 335-534.

- D’Hooghe, D. (2018). Congress workshop: I love you, my killer: “Invisible” attachment trauma resulting in adult traumatic bonding and healing strategies. ISSTD 35th Anniversary Conference, Bridges to the future. Chicago, Illinois.

- D’Hooghe, D. (2020). Workshop: Invisible attachment trauma. Sint-Laureins, Belgium.

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York: Other Books.

- Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14, 387–422